Java streams like never before: Part 1

Introduction⌗

Have you ever looked at a beautiful Java stream sequence and wondered how is it implemented? or wondered how is it possible to implement something similar, with declarative and fluent API with the ability to switch the execution model from sequential to parallel for any data source by changing just a method call? I sure have, and today I will try to explain how the overall plumbing of the API works, and some of the notable places you might want to take a closer look at, This post is going to be harder to grasp (If you’ve never seen this before yourself), I’d suggest you get an IDE open, a cup of tea/coffee and try to read it twice, and stop and look at the JDK’s source code the moment it stops making sense.

Here we go…

Spliterators⌗

Before starting we start looking at streams, I think we should start at the

the foundation of what made streams easily parallelizable, because in my opinion

that wouldn’t have been the case if the Java architects (Brian correct if I am

wrong here) decided to build on the famous Iterator<E> API.

Spliterator<E> is a nice data container with the special ability to split when

the runtime can see fit.

The Spliterator<E> API has no relation to the Iterator<E> one, it offers

a bunch of methods, but we will be most interested in 3:

Spliterator#trySplit: This method allows for splitting the Spliterator instance into 2 parts, where we can execute computations on each part individually, this partitioning can be beneficial when running in a multithreaded environment as some operations can benefit from parallel execution.Spliterator#tryAdvance: This method will allow consuming Spliterator elements one by one with each call, until the Spliterator (or at least the underlying data source) is exhausted.Spliterator#forEachRemaining: This method is a call to thetryAdvancemethod but it keeps on going until exhausting the Spliterator content entirely.

Class Hierarchy⌗

Disclaimer: I may use the words: stream and pipeline interchangeably.

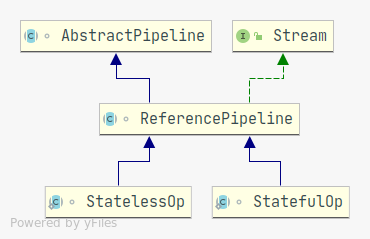

The main implementation of the Stream<E> interface is the

ReferencePipeline<E> class which contains implementations for most operations,

most if not all the of intermediate operations (also called stages) inherit from

the ReferencePipelineclass (unless the pipeline’s content is a primitive type

pipeline. more on that later).

Every pipeline instance keeps track of (omitting some for brevity):

- The source pipeline and the parent pipeline.

- The operations flags in the form of a bitfield.

- The next pipeline.

- The source Spliterator | source Supplier.

- Flag to indicate whether parallel or not.

- The depth of the current pipeline (i.e the number of operations until now).

There are two special implementations of the ReferencePipeline that are worth

pausing to look at:

Head<E>: This implementation is mainly a marker class, to differentiate between an intermediate operation and the start of the pipeline.Sink<E>: An enhancedConsumer. it represents the intermediate and terminal nodes through which the data flows inside the stream, it offers flow control methods such asaccept(int, long, double, Object),begin(int)andend().

Intermediate operations inside a stream can be split into 2 categories:

Operations that do not require state other than the current element at hand, such as

mapfilter… These operations are represented by theStatelessOpclass.Operations that do require state other than the current element at hand, such as

distinctsorted… These operations are represented by theStatefulOpclass.

The data flow⌗

Now that we looked at the major component in the stream API, let’s explore how the data flows through the System, and to make it simple, let’s use an example for reference:

Stream.of("1", "2", "3")

.map(Integer::parseInt)

.filter(v -> v % 2 == 0)

.forEach(System.out::println);

In this simple example, we want to transform all the String elements to integers and only keep the ones that are even and then print the result.

Keep in mind that without actually calling the forEach terminal operator, the

Stream won’t perform any operation, hence the laziness.

Let’s start from the moment we create the stream and we follow the data flow, we

create the stream using the Stream#of method, which will return a new instance

of Head<E> created from a Spliterator with the array/varargs passed as the

source.

Note: The JDK comes with a bunch of Spliterator implementations that are very good

for most use cases (in this example it’s the ArraySpliterator<E> that was

used), but nothing is stopping you from creating your own, and

creating a stream out of it is as simple as calling StreamSupport#stream.

Above I mentioned that execution starts only when the terminal operator is called, which means that from the last operator we see the stages in reverse order, i.e:

ForEeachOp<T> --> FilterOp<T> --> MapOp<E, T> --> Head<E>

with the arrow representing a parent relationship, but we need to execute the operations in reverse order, i.e:

Head<E> --> MapOp<E, T> --> FilterOp<T> --> ForEachOp<T>

Now, what we need to understand is that calling the forEach method on

a sequential stream will call an internal method called evaluateSequential,

and this method will flip the stream nodes by walking the stream nodes backwards

and linking it in the order we expected to execute before performing the actual

operations on the underlying data source. here is the piece of code that performs

this operation:

[1]

@Override

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

final <P_IN> Sink<P_IN> wrapSink(Sink<E_OUT> sink) {

Objects.requireNonNull(sink);

for ( @SuppressWarnings("rawtypes") AbstractPipeline p=AbstractPipeline.this; p.depth > 0; p=p.previousStage) {

sink = p.opWrapSink(p.previousStage.combinedFlags, sink);

}

return (Sink<P_IN>) sink;

}

As mentioned before each Sink can represent an intermediate operation, and has

a reference to the next Sink in the pipeline.

Every call to accept on a Sink

instance is equivalent to performing the operation that the Sink represents and

possibly pushing the resulting elements to the next Sink in the pipeline.

Let’s look at the map and filter examples.

// map implementation

@Override

Sink<P_OUT> opWrapSink(int flags, Sink<R> sink) {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<P_OUT, R>(sink) {

@Override

public void accept(P_OUT u) {

downstream.accept(mapper.apply(u));

}

};

}

Calling opWrapSink on the Sink representing the map operation in [1] will

create a ChainedReference which is nothing moew than a Sink that has a reference to

the next Sink just like a linked list.

The accept operation is where the actual operator logic resides, in this case, map takes

a function and applies it to the current element and that’s exactly what the

mapper.apply(u) call is for.

Also, notice that the result is not returned, but it’s passed as

a parameter to a downstream, which is the next Sink in the pipeline, in this

case the filter operator.

// filter implementation

@Override

Sink<P_OUT> opWrapSink(int flags, Sink<P_OUT> sink) {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<P_OUT, P_OUT>(sink) {

@Override

public void accept(P_OUT u) {

if (predicate.test(u))

downstream.accept(u);

}

};

}

The filter operator implementation is similar, but this time, depending on the

result of the predicate (A Predicate is a function that given an element

returns true or false) will determine whether to push the element down the

pipeline or not.

Confused? Let’s try another example, this time with a StatefulOp.

// distinct implementation

@Override

Sink<T> opWrapSink(int flags, Sink<T> sink) {

Objects.requireNonNull(sink);

if (StreamOpFlag.DISTINCT.isKnown(flags)) {

return sink;

} else if (StreamOpFlag.SORTED.isKnown(flags)) {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<T, T>(sink) {

boolean seenNull;

T lastSeen;

@Override

public void begin(long size) {

seenNull = false;

lastSeen = null;

downstream.begin(-1);

}

@Override

public void end() {

seenNull = false;

lastSeen = null;

downstream.end();

}

@Override

public void accept(T t) {

if (t == null) {

if (!seenNull) {

seenNull = true;

downstream.accept(lastSeen = null);

}

} else if (lastSeen == null || !t.equals(lastSeen)) {

downstream.accept(lastSeen = t);

}

}

};

} else {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<T, T>(sink) {

Set<T> seen;

@Override

public void begin(long size) {

seen = new HashSet<>();

downstream.begin(-1);

}

@Override

public void end() {

seen = null;

downstream.end();

}

@Override

public void accept(T t) {

if (seen.add(t)) {

downstream.accept(t);

}

}

};

}

}

The distinct operator is essentially doing the same thing, but as you can see

there are some differences:

- The intermediate state is kept: The operator can keep an internal

Set, that in the worse case where all the elements coming from the source are all distinct, will contain eventually all the elements in the stream. - The algorithm is different: The codepath to be executed is chosen depending on the flags associated with the incoming stream Flags and we will discuss the usage and the Why behind it in the next section.

Flags⌗

Flags are lightweight markers (basically a bitmask) that describes the characteristics of a stream, they hold information about the content of the stream and the operations that have been carried out on it, example: are the stream elements distinct? are the stream elements sorted? are the stream elements sized? …

Flags are invisible to the user of the stream API, but they can be very helpful for the underlying stream framework, to control and optimize computations.

Internally each stream operation will hold a bitmask (i.e an integer) that represents the current characteristics of the current stream, this value is carried out and changed through successive operations applied to the stream parts, let’s look at an example:

The sorted operation sorts the elements of the stream then pushes them to the

downstream in sorted Natural order, but it also sets the bit (or the Flag)

that marks the current output stream as SORTED so that information can be used

in later operation to optimize execution speed or memory usage.

OfRef(AbstractPipeline<?, T, ?> upstream) {

// Note that we are carrying the flags indicating that the stream is

ORDERED and sorted.

super(upstream, StreamShape.REFERENCE,

StreamOpFlag.IS_ORDERED | StreamOpFlag.IS_SORTED);

this.isNaturalSort = true;

// Will throw CCE when we try to sort if T is not Comparable

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

Comparator<? super T> comp = (Comparator<? super T>) Comparator.naturalOrder();

this.comparator = comp;

}

....

@Override

public Sink<T> opWrapSink(int flags, Sink<T> sink) {

// If the input is already naturally sorted and this operation

// also naturally sorted then this is a no-op

if (StreamOpFlag.SORTED.isKnown(flags) && isNaturalSort)

return sink;

else if (StreamOpFlag.SIZED.isKnown(flags))

return new SizedRefSortingSink<>(sink, comparator);

else

return new RefSortingSink<>(sink, comparator);

}

This is the implementation of the sorted operator in the OfRef<T> class,

a couple of things worth looking into here:

The flags are carried out to indicate to future operations that the current stream is now

ORDEREDandSORTED.Flags will help optimize the execution of this operator, in 2 ways:

- If the stream is already sorted, there is nothing to be done and a reference

to the current sink is returned with no changes, this is where some of the

laziness in the stream API comes, the framework is written in such a way

that it only performs computation when it needs to, for example, if we

write this:

Stream.of(...).sorted().filter(...).sorted().sorted()this will onlysortonce, it looks weird now, why would someone call sorted more than once, but if this is across method boundaries and you don’t own the code returning the stream, and you don’t know if it has been sorted, you may end up callingsortedon an already sorted stream, but the nice thing is most of the time you don’t care because you won’t pay for it because of the way streams are implemented. - If the stream is sized, and array with fixed size is used (Take a look at

SizedRefSortingSink) to optimize memory usage, otherwise a dynamic array is used (ArrayListin this case).

- If the stream is already sorted, there is nothing to be done and a reference

to the current sink is returned with no changes, this is where some of the

laziness in the stream API comes, the framework is written in such a way

that it only performs computation when it needs to, for example, if we

write this:

The stream framework is doing very nice optimizations to relieve the developer from having to think about such details and only worry about what he is trying to achieve.

If this still looks confusing, let’s take a look at another operator:

distinct.

...

// This is an annonymous inner class representing the distinct operator

return new ReferencePipeline.StatefulOp<T, T>(upstream, StreamShape.REFERENCE,

StreamOpFlag.IS_DISTINCT | StreamOpFlag.NOT_SIZED) {

...

if (StreamOpFlag.DISTINCT.isKnown(flags)) {

return sink;

} else if (StreamOpFlag.SORTED.isKnown(flags)) {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<T, T>(sink) {

boolean seenNull;

T lastSeen;

@Override

public void begin(long size) {

seenNull = false;

lastSeen = null;

downstream.begin(-1);

}

@Override

public void end() {

seenNull = false;

lastSeen = null;

downstream.end();

}

@Override

public void accept(T t) {

if (t == null) {

if (!seenNull) {

seenNull = true;

downstream.accept(lastSeen = null);

}

} else if (lastSeen == null || !t.equals(lastSeen)) {

downstream.accept(lastSeen = t);

}

}

};

} else {

return new Sink.ChainedReference<T, T>(sink) {

Set<T> seen;

...

The constructor of the class as before makes sure that next operations knows

that the resulting stream from this operation is DISTINCT, what’s new here is

that it also passes a new flag NOT_SIZED, this flag clears the IS_SIZED

flag, i.e next operations won’t see the resulting a stream as having a size,

this is simply because if there are duplicates in the values of the stream, the

source size is going to change and attempts to use the old size of the source

stream will result in erroneous operations.

You can not also that if the stream is already marked as DISTINCT just like

before, nothing is performed, but if it’s sorted, we know that we can make it

distinct by using O(1) extra memory, otherwise we fall back to a Set based

approach.

From above I hope that you now have a better understanding of Flags and how is the Stream API is making a lot of the optimizations on your behalf so that you can focus on what you do best.

Conclusion⌗

The Stream API is a nice piece of software that is well designed, and tested, and one can learn a lot of things when reading the underlying code, not everybody should do that of course, but it’s a nice learning experience.

In this post we talked in terms of Sequential execution, In another post we will take a look at how the API handles Parallel execution, what are the challenges that the designers faced? and how did they overcome them?