Distributed systems chronicles: Key value store (4) - Replicated storage

Introduction⌗

In the previous post, We added the final touches in our single node key-value store, in this post we will discuss what are the problems with a single node architecture, and how Consensus algorithms can help us solve these problems.

Single point of failure⌗

Our implementation of a key-value store works well, yet what happens if the machine hosting the server goes down? One might think that we can run multiple instances of the same server, that would be the way to go, but how can we make these multiple instances synchronize? multiple concurrent users writing to all of the instances would cause each server to receive a bunch of interleaved messages, Which order is the right one to be executed on each node? How can we be sure that the same Order and the same write requests are being processed in all of the servers?

Adding more servers increases our availability, but makes having a consistent view of the systems is very hard to achieve. Luckily we have Consensus algorithms to help us with that.

Consensus algorithms⌗

Consensus in distributed systems can be viewed as the ability of multiple components (servers in this case) to reach an agreement on some shared state, while taking into consideration that machines can fail (as it’s the case for all hardware) and networks used for communication can fail as well (due to hardware damage, or other factors).

Consensus algorithms should also deal with component recovery (the same instance stared in some other machine, network partition healed …).

The father of all Consensus algorithms is the Paxos algorithm, which is notoriously known for being hard to grasp, and also its initial paper left a lot of the implementation details up to the reader. Raft (which we will be using in our implementation) is a more Understandable and approachable Consensus algorithm, and it’s paper described in a relatively good amount of detail the implementation aspects of the algorithm, and the writers even gave a model implementation of the algorithm, since then, a lot of libraries in different programming languages tried to implement the language and the Raft website lists quite a bunch of them.

Raft is widely used in production systems, some examples might be etcd which a key-value store that is used within Kubernetes clusters, Consul a service registry that uses Raft to guarantee a high degree of availability…

Raft⌗

Disclaimer: The information presented in this section is all from the Raft paper (while omitting some of the details for simplicity), if you are writing a Raft implementation, please read the full paper.

Replicated state machine⌗

Raft’s primary premise is the ability of synchronizing operations on a data structure (state machine) across multiple servers (replicated).

The state machine can be anything, for our purposes of making a key-value store,

it’s the Storage implementation itself.

The flow⌗

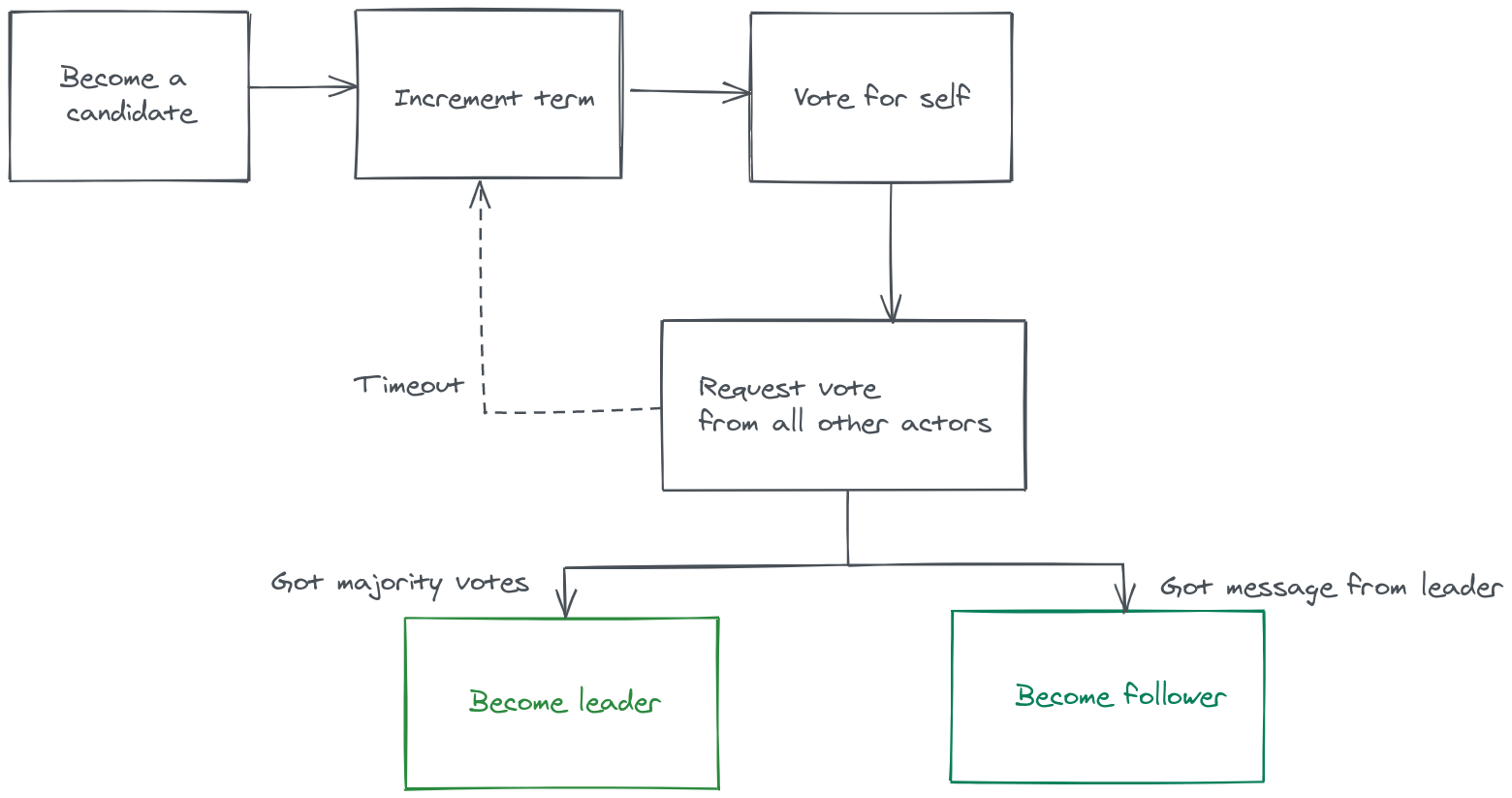

The flow of a Raft run (i.e Term in Raft lingo), starts with every node being in

the follower state, the followers have random timers that keeps decrementing

until they expire and then they promote themselves to a Candidate state, at

that point the candidate seeks the votes of every node in the cluster (including

itself), if a node gets a majority of votes: majority_votes = (cluster_nodes + 1) / 2, it will be promoted to a leader state

and immediately starts sending heartbeats to the other nodes.

Candidates that receive a heartbeat from a leader, transition back to the follower state and resets their election term (if required), and election timeout.

Followers that receive heartbeats from the leader, update their election term (if required), and reset their election timeout.

This keeps on going until the leader becomes unavailable, at that point this whole dance repeats again.

Of course this the general “happy path”, there are more subtleties to the flow but we won’t go into too much details, but the important thing for me in this post is that you understand the Raft Components/Actors and the execution flow, If you are more of a visual learner, this visualisation would guide you through the above described flow.

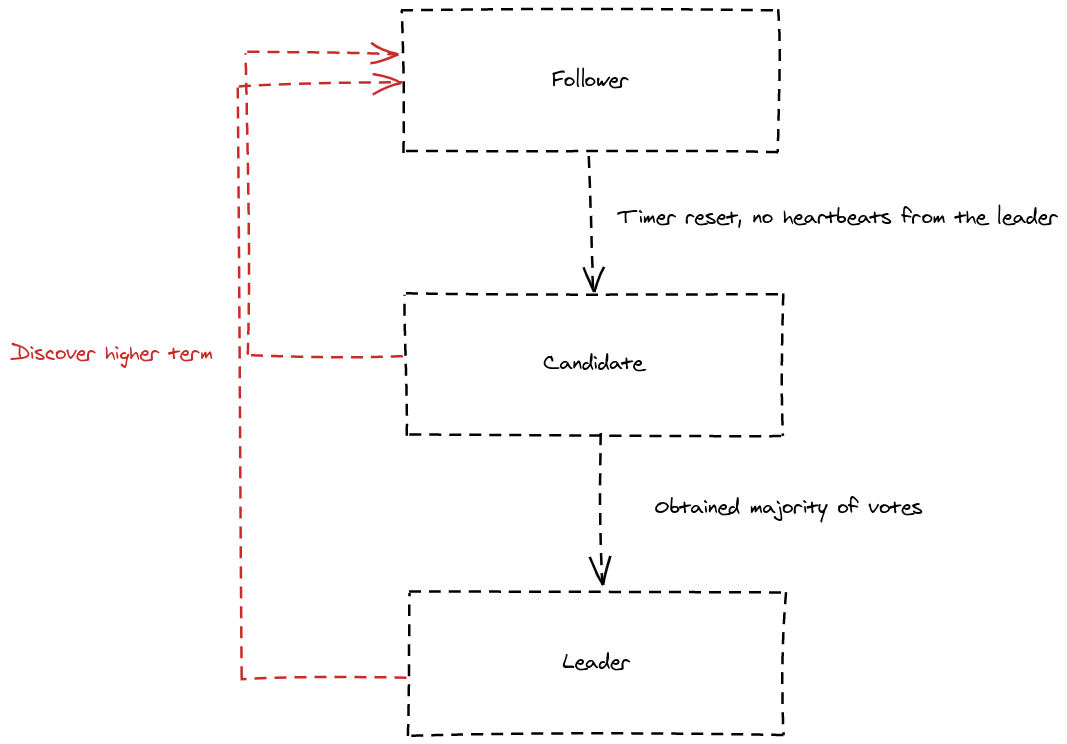

So as described above, A Raft node (server) can be in one of 3 states:

Follower: Passive actors, the leader tells them what they should do, and they expect regular heartbeats from him.

Candidate: A candidate node seeks to be the next leader, it sends requests to the other nodes to tell them that he is a candidate and he needs a vote.

Leader: A leader node is a candidate that got the majority of votes during the last election term, he is responsible for replicating the log, and he is supposed to send regular heartbeats to all of the followers to maintain his role as a leader.

Terms⌗

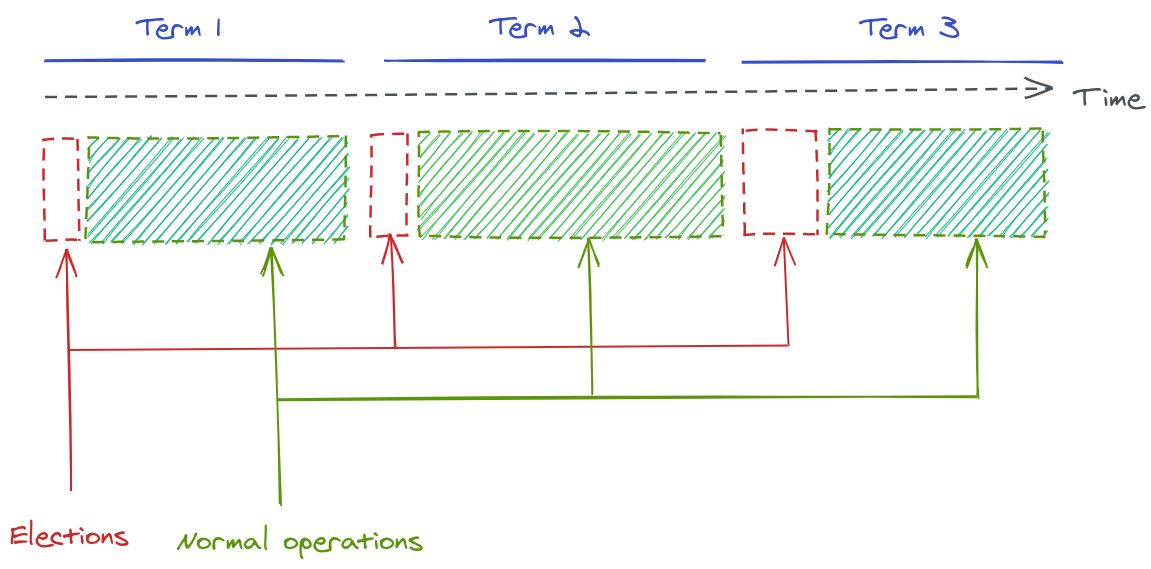

The period between each election round is called a Term:

Each term can have at most one single leader This implies that there can be a case where no leader has been elected due to a split vote, which would cause the actors to start a new term in an attempt to elect a leader.

The terms are exchanged between every message/RPC call between the actors, every actor has its own term (Which is synchronized with the leader’s term), so no global view is maintained (Raft does not enforce clock synchronization between the servers), If in some message exchange an actor found a term later than it’s own, it will update its own term and it will revert to a follower state (if it was in a leader state that is).

Another nice benefit of terms is that they indicate obsolete information, i.e if an actor received a command with an obsolete term, it should return an error, because this means that the sending actor has crashed or was in a network partition that caused him to stay on an older term, returning an error is an indication to the actor to maybe become a follower because his term is obsolete.

Log replication⌗

Node’s Log⌗

Every node has a Log data structure, to keep track of the received commands, the

log can be seen as non-volatile Vector<LogEntry>. Every entry in the log will

contain the received command from the client as well as some book-keeping

information for safety and consistency guarantees, a LogEntry could look

something like:

struct LogEntry {

// The term at which this entry has been received

Term: u64,

// The raw command bytes

command: Vec<u8>,

...

}

Executing client commands⌗

All the commands in a Raft cluster go through the leader, if a follower node receives a client request, it can either return an error, or forward the request to the leader.

When the leader receives a new client command, it adds a new LogEntry

to it’s log, and sends parallel RPCs to all of the other nodes to add the same LogEntry to their

logs as well, once a log entry is replicated across a majority of nodes, it is considered committed,

The leader then can apply the command to it’s state machine and return back to

the user, and the other nodes can commit the log entry as well.

The replication/heartbeats RPC is called AppendEntries by the paper, the

parameters to the call can be seen as:

struct AppendEntriesRequest {

// leader's term.

term: u64,

// Index of log entry immediately preceding new ones.

previous_log_index: u64,

// Term of prevLogIndex entry.

pervious_log_term: u64,

// Log entries to store.

// Heartbeat requests have an empty entries array.

entries: Vec<LogEntry>,

// The Leader’s commit log index.

leader_commit: u64;

}

Example⌗

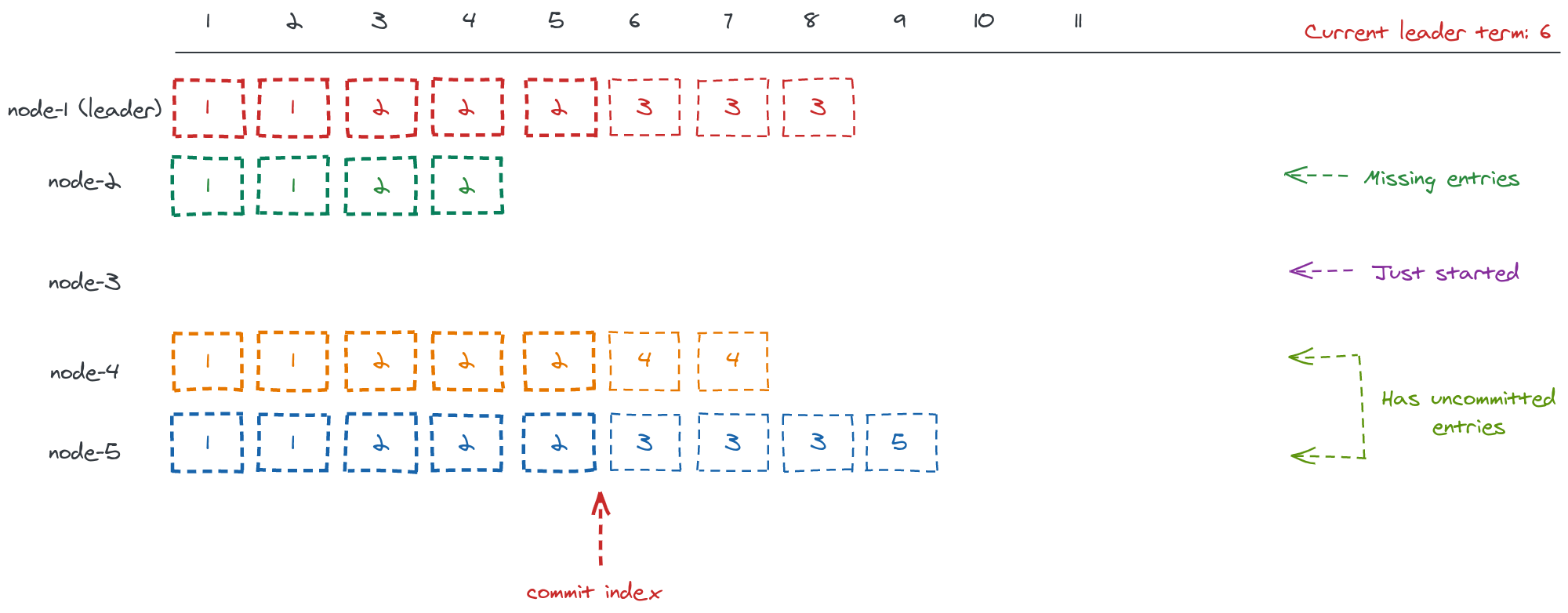

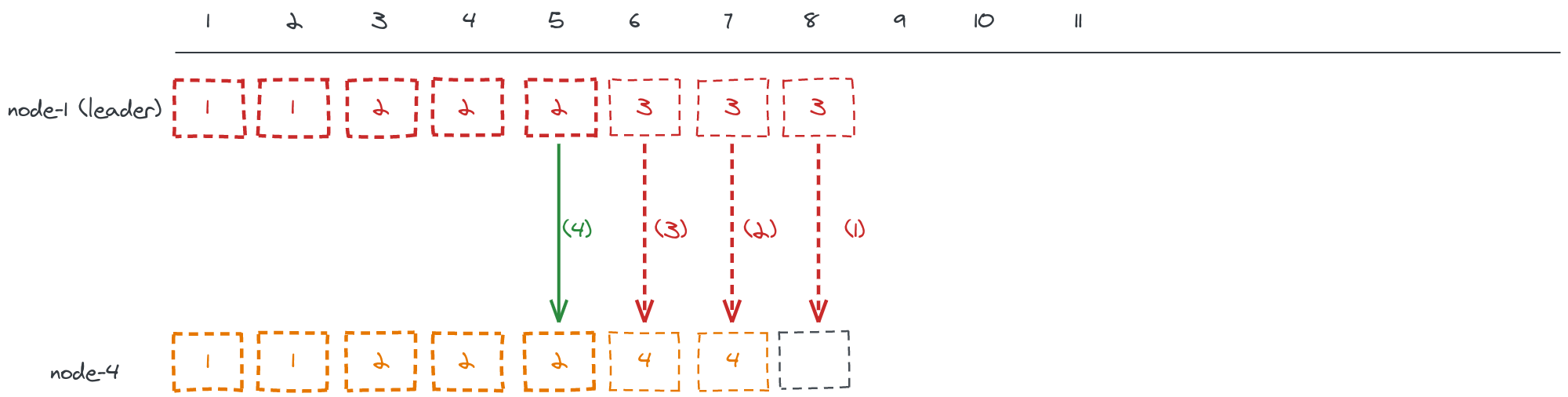

Let’s take a look at an example of how a newly elected leader might replicate it’s log to all other servers, let’s imagine that the current log state is the following:

All entries up to lindex 5 are committed, and node-1 has been elected leader.

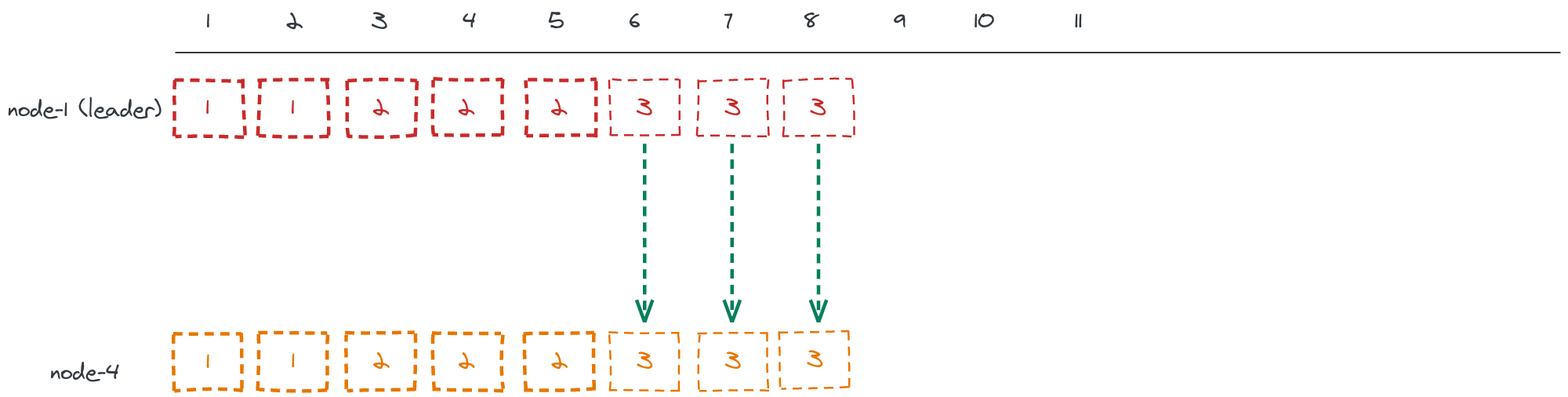

Once elected, every leader tries to replicate it’s log to all other nodes, i.e At some point eventually all logs will look like the leader’s log.

To simplify, let’s look at how the leader will replicate it’s log to node-4, while keeping in mind that it will do the same thing for all of the other nodes.

The leader will keep sending AppendEntries RPC calls (1) (2) (3) to the node to find the

first index in the node-4 log that have been written at the same term as an

entry at the same index in the leader’s log, in this case it’s index 5.

Once that index is found, the leader is sure that all replicated entries up to

that point are exactly the same in both logs, so all it has to do is to

replicate it’s log from that index + 1 onwards.

Conclusion⌗

In this blog post, we did a theoratical summary of the Raft protocol, and how it can be used to replicate state machines accross different computers, the next post will dive into more details on how to integrate the Raft protocol to build a distributed version of our key-value store.

Stay tuned!